No Stone Left Unturned

- No Stone Left Unturned

- Play the prototype on GD Games now…

- Instructions

- Mentions

- A Summary of Research

- YouTube Videos

Play the prototype on GD Games now…

https://gd.games/games/09e2f433-e3bb-46f4-8d16-2d2ab685d834

Instructions

- I recommend playing fullscreen

- W A S D to move

- Enter to move dialogue along, up and down arrows to choose options, space to speed up text and confirm choices

- Walk into items to collect them

- Press R when touching a sign to read it

To learn more about the Avebury Papers project, please visit: https://www.aveburypapers.org/

Mentions

- Winner 2025 University of York Open Research Award

- Time Team Podcast Appearance

- The Avebury Papers Blog

- Council for British Archaeology Early Careers Conference

- The Interactive Pasts Conference 4

A Summary of Research

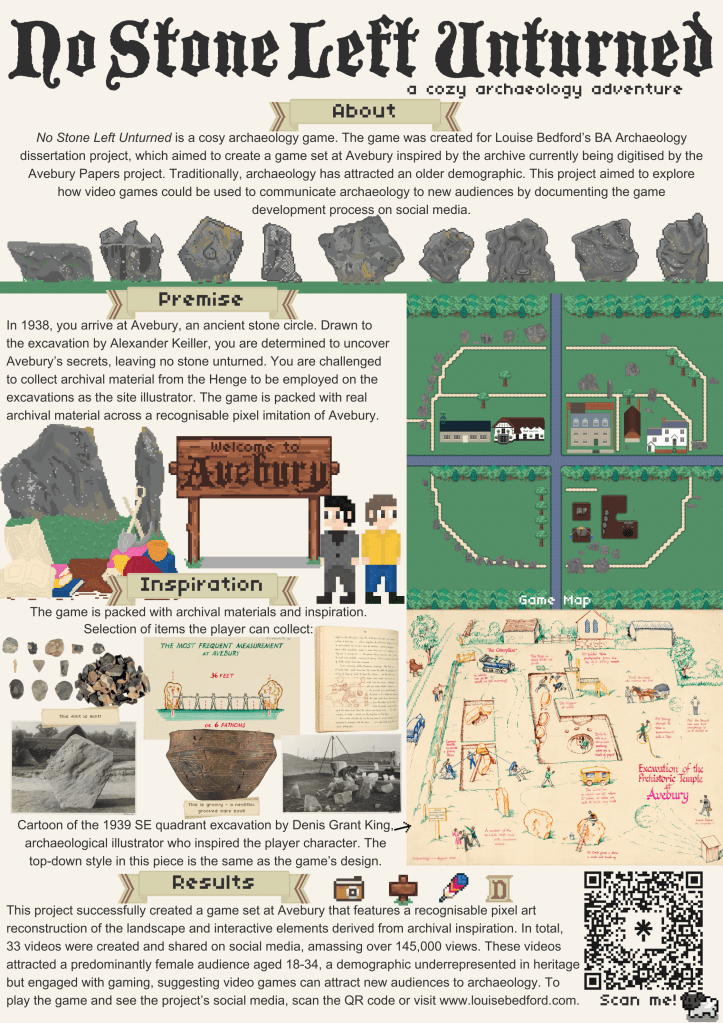

Traditionally, archaeology has attracted an older demographic. Video games and social media provide an opportunity to communicate archaeology to new audiences. This project for my undergraduate dissertation aimed to create a game set at Avebury Henge, inspired by the archive currently being digitised by the Avebury Papers project, and to document the process on social media.

Avebury is an optimal location for such a study. Avebury Henge is a Neolithic monument located in Wiltshire, England. The site is of international significance due to its scale and exceptionality. Built and altered between 2850 and 2200 BCE, the site today includes a massive henge, which is a bank and ditch, with the world’s largest stone circle and two smaller stone circles within. The village of Avebury was later built inside the monument. The site attracts more than 250,000 visitors a year, but can be difficult to fully visualise. The only major excavations undertaken at Avebury ended abruptly due to the outbreak of World War II, and consequently, lots of material has been under-analysed. The Avebury Papers project is a four-year project to digitise, explore, and share the multimedia archive of Avebury’s Neolithic origins and its subsequent life history. In addition to the various archaeological materials, the archive also includes creative works inspired by Avebury, providing narratives that are equally important as the stones to understanding Avebury today. At the end of the project, the entire archive will be made available online and open access for anyone to use for research or creative purposes. Creating a game explored the potential of incorporating archival materials into creative projects, and while studies with insights into the archaeologist as a creative maker are rare, it is a valuable process.

Game Development

Archival research was the foundation for game development inspiration. An exploratory approach was used to examine the Avebury Papers archive and identify material to incorporate into gameplay. Following the initial idea generation, the game development process was structured using a Game Design Document (GDD). A GDD is like a recipe for game development, which provides a structured plan that evolves throughout the production process.

The development of a GDD created a clear project scope:

- To create a cosy, 2D top-down pixel art reconstruction of Avebury Henge during the 1938-39 excavations.

- Including interactive elements, such as signs, photographs and artefact spots.

Due to limited time, the game’s final version focuses on a playable prototype that could later be expanded with more gameplay mechanics.

The game was designed within the cosy genre, a broad category of games designed to be relaxing, casual, and comforting. The demographic of players is wide-ranging, but it is believed to skew toward women in their 20s and 30s. This demographic is underrepresented in heritage and archaeology, making this genre an appropriate choice, as developing a cosy game could introduce archaeology to new audiences.

The game was developed using two tools: GDevelop and Aseprite. GDevelop is a game engine, a type of software used to construct games. It was chosen because it is no-code and open-source, which makes it an accessible option. Aseprite is a specialised pixel art drawing software used to create the game’s assets.

The first development stage was creating the game world, a recognisable pixel art reconstruction of Avebury Henge from a top-down perspective. This was achieved using maps, photographs and Google Earth to develop a recognisable plan that captured the character of Avebury. A scaling system was also designed to ensure consistency. This translates to:

- 16 pixels = ~1 metre for key objects, such as buildings, stones and characters.

- 16 pixels = 2-5 metres for landscape elements, allowing for necessary compression but maintaining recognisability.

Once the game map was complete, interactive elements were added. These include information signs, artefact spots, photographs and drawings. The ideas for these were derived from the original archival research and were essential to fulfilling the aim of creating a game inspired by the Avebury Papers archive.

Content Creation

Alongside game development, documenting the process on social media was a key part of this project with the aims of attracting new audiences, generating engagement and providing a reflective space for assessing the development progress. This methodology incorporates principles of open archaeology, which aims to make archaeological research accessible to the public.

The open research principles of this research were formally recognised and awarded the University of York’s Open Research Award.

A total of 33 videos were created and shared across TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube.

The game’s premise is as follows: In 1938, the player arrives at Avebury without knowing how long they will stay. Drawn to the archaeological excavations led by the marmalade magnate Alexander Keiller, they are determined to uncover Avebury’s secrets, leaving no stone unturned. They play as the real archaeological illustrator, Denis Grant King, and have a cosy archaeological adventure as they explore this prehistoric world through items from the Avebury Paper archive. The game begins with an introduction setting the scene for gameplay, which leads into dialogue with Keiller greeting the player on their arrival at Avebury. Keiller then challenges the player to collect resources he has scattered across the site to prove they are worthy of employment on his excavations. The player can collect a total of 57 items, including artefacts, signs, drawings, notes and photographs. Once the player has collected all the items, they can return to Keiller, who then hires them to work on the excavation.

Building Avebury

Creating a game world that was recognisably Avebury was essential. To create this world, a variety of archival and contemporary sources were used. However, like most archaeological interpretations, the game world of No Stone Left Unturned is subjective and open to critique. The medium of a pixel video game with a top-down perspective provides an alternative representation and experience of Avebury. This is beneficial because in person, the site can be difficult to visualise. While recognisable, this reconstruction of Avebury is not photorealistic, but can be viewed as immersive and contextually engaging rather than strictly accurate. The most time-consuming part of building the world was creating all 42 stones individually, with some taking up to an hour to complete. This level of detail may be where my approach as an archaeologist creating a game differed from that of a game designer, as they might not have deemed this necessary. However, it was an essential choice that added to the depth and immersion of the world.

Changes to my view of Avebury

The process of developing a game provided me with a framework to explore Avebury Henge and its archive. This allowed me to engage with the site in a way I had never done before and ultimately changed my view of it.

For example, I had viewed the stones of Avebury as a collective. However, the time-consuming process of recreating each stone for the game world made me think about them individually. This change in perspective made me consider how Avebury developed over time. The monument was not built in a single event but instead was modified over centuries. It likely would have taken hundreds of years just to erect the stones, and some estimates suggest there were originally over 700 stones making up monuments in the Avebury landscape. Each stone is also unique; this raises interesting questions of why specific stones were selected and erected? Do their shapes and locations hold specific significance? It has been previously suggested that Avebury’s broader and narrower shaped stones represent female and male forms. In studies of Upper Palaeolithic cave art, pareidolia, the psychological phenomenon of seeing familiar shapes in random objects, has been proposed as a reason for the artwor. Could similar arguments be made for the selection of stones in Neolithic monuments? A game looking at the development of Avebury could be interesting to explore these questions further.

Incorporation of Archival Materials

The incorporation of archival materials into gameplay was successful, with the archive lending itself well to gameplay incorporation. The interactive elements in the game are mostly all directly from the archive. The following examples have been selected to illustrate the effectiveness of archive incorporation. Denis Grant King was an archaeological illustrator and avid diarist who documented the 1938-39 excavations at Avebury. His diary entries and drawings that are housed in the archive heavily influenced the game’s narrative and design, so much so that he was chosen to be the player character. For example, the game’s premise and introductory text sequence are inspired by the real introduction to King’s diary. The personal experience captured in King’s diary of experiencing and working at Avebury makes it an ideal narrative basis for a game. King also states he was “determined to leave no stone unturned,” which inspired the name of the game, ‘No Stone Left Unturned’.

Furthermore, in the game, King wears a yellow shirt, and even this is derived from archival inspiration. In a diary entry, King details how he wore a yellow shirt one day, which caused a lot of amusement at the site; Keiller even took a colour photograph, and King later joked he did this “presumably as an archaeological exhibit!”, which is referenced in the game. King also illustrated a cartoon of the excavation of the southeast quadrant of Avebury in 1939. The top-down style in this piece is the same as the game’s design.

While King provided a lot of inspiration, his role as the player is problematic. His diary includes several outdated beliefs, including antisemitism, phrenological analysis of acquaintances and use of various xenophobic slurs and generalisations, all of which were omitted from gameplay. King is also a white man in the 1930s, meaning his experience of Avebury will be very different to that of a lot of society today. His role as a player may also encourage stereotypes of archaeology, as archaeologists in popular culture have traditionally been portrayed as elite white men. Upon reflection, a better choice would be to implement character customisation so the player can choose who they are in the game. Players will then recognise themselves and identify more with the archaeology. This would not impact gameplay, and it solves the issues stated.

Nevertheless, this project highlights the potential of archives for creative-based projects as they offer fascinating resources and narratives that can be explored.

Future developments

Social Media Results

Between 20 June 2024 and 14 March 2025, 33 videos were created and shared across TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube. These amassed over 145,000 views, 5,800 likes and 270 comments.

Unfortunately, there are limited case studies published that evaluate the application and impact of digital outreach strategies by projects. This makes it difficult to benchmark these results to fully comment on the success. However, when compared to one case study, I did note my project received an average of 213 more views per YouTube video in a three times shorter period.

Demographic data also revealed something different than found in other projects. The demographic data revealed a predominantly female audience aged 18-34, which is a demographic underrepresented in heritage but engaged with gaming, suggesting I did achieve my goal of attracting new audiences. The engagement metrics reflect success in attracting new audiences and generating engagement, despite the campaign being short and niche.However, I do think that more research needs to be done in this area.

A limitation this project experienced was time. Balancing content creation and game development resulted in a large workload. While this project utilised three platforms, it could have been more beneficial to focus on one platform due to the nuances between them. It is difficult to determine the ideal platform; however, in this project, TikTok had the highest engagement, which suggests it is effective for communicating archaeology to new audiences. However, finding success on social media may depend on the type of content and its aims.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research demonstrates how archaeology and archives can be explored through creative projects and how video games and social media have the potential to communicate archaeology to new audiences.

YouTube Videos

TikTok and Instagram @louisearchaeology