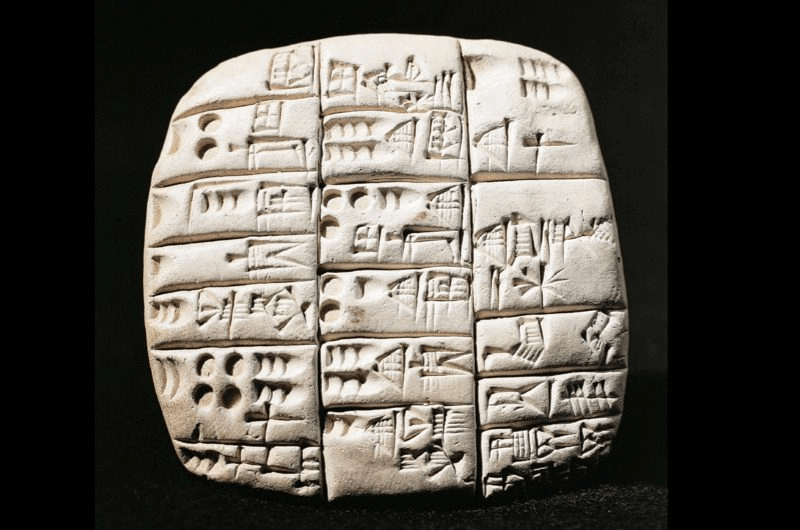

Cuneiform is the earliest form of writing, beating Egyptian hieroglyphics by an estimated few hundred years. Around 3200 BCE, in the late Neolithic period, it was invented by Sumerian scribes in the ancient city-state of Uruk, in present-day Iraq, as a means of recording transactions. From the early Bronze age, it was in active use.

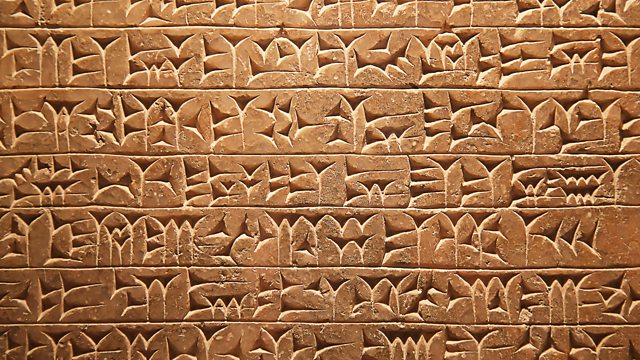

Cuneiform itself is not a language but instead, a writing system used to write a multitude of languages. All of the main Mesopotamian civilizations used versions of cuneiform to write their languages, these include but are not limited to Sumerians, Babylonians, Elamites, Assyrians and Akkadians. Akkadian cuneiform texts appear from 2400 BCE onwards and account for the bulk of the cuneiform record. Furthermore, Akkadian itself was adapted to write the Hittite language in the early 2nd millennium BCE.

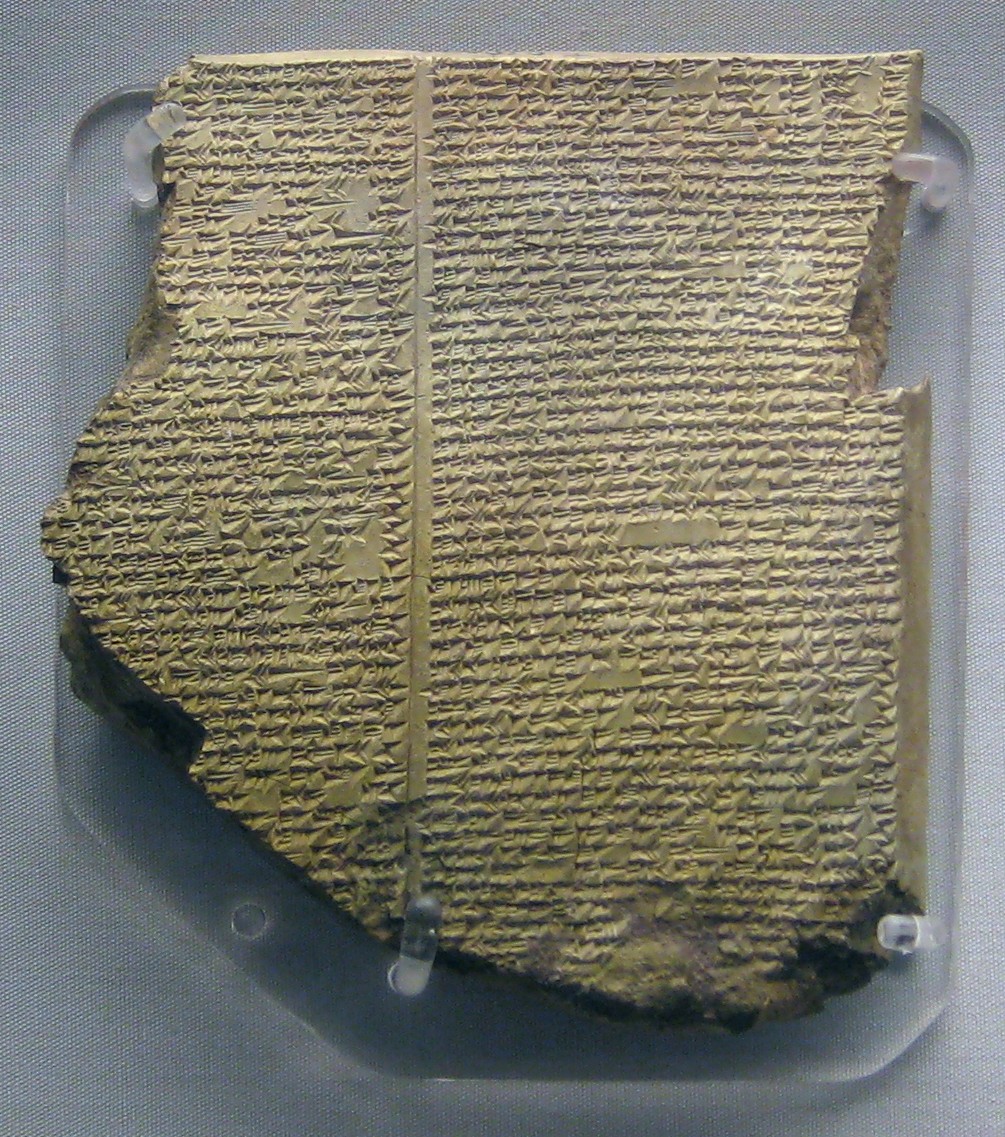

Texts were written with a reed stylus which was pressed into soft clay tablets to create the indentations that make up the scripts.

Why is it called Cuneiform?

The name comes from the Latin for wedge-shaped with cuneus for ‘wedge’ and ‘forma’ for shape, due to the wedge-shaped style of writing.

When did Cuneiform stop being used?

Gradually, cuneiform writing was replaced by the alphabetic system and, by the 2nd century CE, the script was extinct after around 3,000 years of use. The latest known cuneiform tablet dates to 75 CE. Absolutely all knowledge of how to read the writing was lost until the deciphering began in the 19th Century.

How was Cuneiform deciphered?

For many centuries, travellers to ancient ruins in the Middle East, have noticed what is now known to be carved cuneiform inscriptions and have been intrigued by these. For example, in the 15th Century Giosafat Barbaro, a Venetian diplomat returned from the Middle East with news of odd writing carved in the temple of Shiraz and on many clay tablets.

Pietro Della Valle, an Italian composer & author, had travelled around Mesopotamia between 1616 and 1621. In 1625, he brought back to Europe copies of characters he had seen in Persepolis, an ancient city in modern-day Iran, Ur, and the ruins of Babylon. The copies he had made were not completely accurate, however, he did understand that writing had to be read from left to right as this followed the direction of the wedges. Yet, he made no attempt to decipher the scripts.

In 1700, Thomas Hyde first called these unknown inscriptions “Cuneiform”, however, he reached the conclusion they weren’t anything more than just decorative friezes.

Old Persian Cuneiform Decipherment

In 1711, the first proper attempts at deciphering the Old Persian variation of cuneiform began as faithful inscriptions, published by Jean Chardin, became available.

In 1767, Carsten Niebuhr published complete and accurate copies of inscriptions at Persepolis in his Reisebeschreibungen nach Arabien (Account of travel to Arabia and other surrounding lands”, these are known as the Niebuhr inscriptions.

Soon after this, it was perceived that out of the 3 types of cuneiform scripts to have been encountered this one (now known as Old Persian cuneiform) was the simplest and, therefore, the best candidate for successful decipherment. This was to be the cast as it was the first cuneiform to be deciphered.

Niebuhr identified that there were only 42 characters in the simpler category of inscriptions, which he named “Class I”, and affirmed that this must therefore be an alphabetic script, this is partially accurate as Old Persian cuneiform is semi-alphabetic. He also identified Class II and Class III, however, he wrongly assumed that all the classes represented the same language, while in fact, the different classes represented a different language as well as a different form of writing. Class I was to be Old Persian cuneiform.

Friedrich Münter, Bishop of Copenhagen, improved on previous work. He proved that the Niebuhr inscriptions belonged to the Achaemenid Empire, which led him to the belief the inscriptions were in the Old Persian language and most likely mentioned the Achaemenid Kings. He also suggested that the long word appearing with high frequency and without any variation towards the beginning of each inscription (𐎧𐏁𐎠𐎹𐎰𐎡𐎹) must correspond to the word “King”.

Georg Friedrich Grotefend, a German epigraphist and philologist, extended this work by realising that a king’s name is often followed by “great king, king of kings” and the name of the king’s father. By looking at similarities in character sequences, he made the hypothesis that the father of the ruler in one inscription would possibly appear as the first name in the other inscription: the first word in Niebuhr inscriptions 1 (𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁) indeed corresponded to the 6th word in Niebuhr inscriptions 2. Then looking at the length of the character sequences, and comparing them with the names and genealogy of the Achaemenid kings as known by the Greeks, also taking into account the fact that the father of one of the rulers in the inscriptions didn’t have the attribute “king”, he made the correct guess that this could be no other than Darius the Great, as his father Hystapes was not a king. These connections allowed him to figure out the cuneiform characters that are part of Darius, Darius’s father, Hystaspes, and Darius’s son, Xerxes. By this method, he had correctly identified each king in the inscriptions.

Despite the groundbreaking implications of this research and method, Grotefend failed to convince other academics, and the official recognition of his work was denied until 1823 when Jean-François Champollion confirmed the discovery. Champollion, who had just deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphs, was able to read the Egyptian dedication of a quadrilingual hieroglyph-cuneiform inscription on an alabaster vase, proving Grotefend correct.

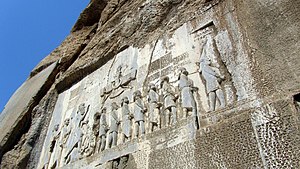

In 1835 Henry Rawlinson, a British East India Company army officer visited the Behistun Inscriptions in Persia. This consists of identical texts in the three official cuneiform languages of Darius the Great’s empire: Old Persian, Babylonia and Elamite. In 1837, he finished his copy of the Behistun inscription; the task of deciphering Old Persian cuneiform texts was virtually accomplished.

Further Translation of other Cuneiform Scripts

Once the translation of Old Persian was complete, Rawlinson and Edward Hincks, an Irish assyriologist, both separately began to decipher the other cuneiform scripts, Babylonia and Elamite, through using the Behistun inscription.

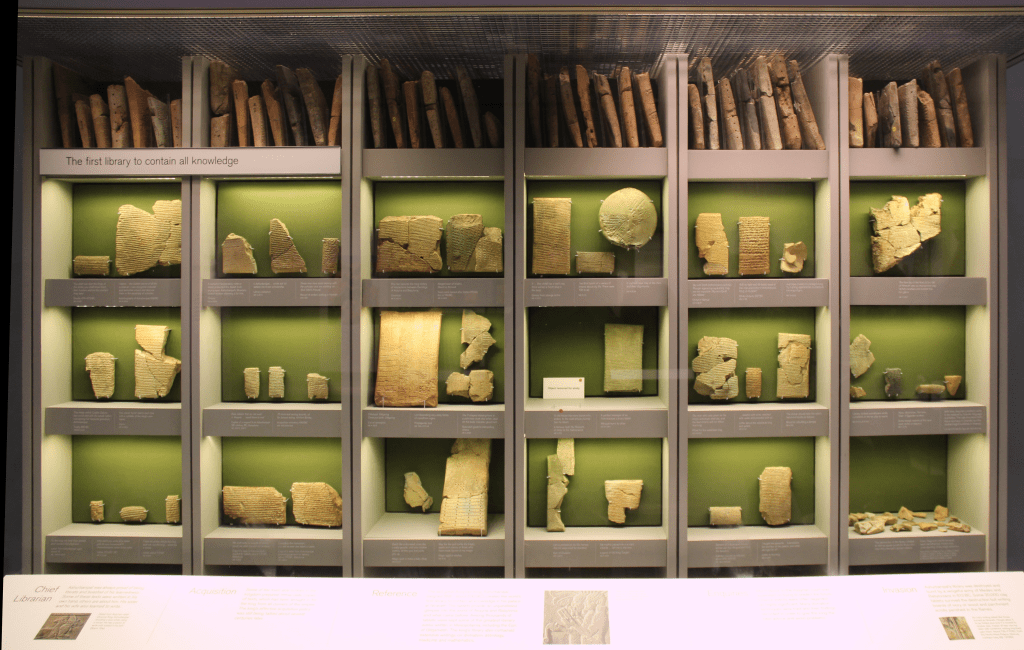

The decipherment of Babylonian ultimately led to the decipherment of Akkadian, which was a close predecessor of Babylonian. Excavations of the city of Nineveh from 1842, greatly helped as it led to the discovery of the Library of Ashurbanipal. These are the remains of 2 libraries discovered in 1849 and 1851, which are now mixed up, which are royal archives containing over 30,000 cuneiform tablets. Helped by this material, by 1851, Rawlinson and Hincks could read 200 Akkadian signs. Soon afterwards, they were also joined in the decipherment by Julius Oppert and William Henry Fox Talbot. In 1857 in London, these 4 men met and took part in an experiment to test the accuracy of their decipherments. Each of them was given a copy of a recently discovered inscription from the reign of the Assyrian emperor Tiglath-Pileser I and had to translate it for a jury of experts, who would examine the results and assess their accuracy. The jury found the translations to all be in close agreement and was satisfied with the accuracy of the decipherment of Akkadian cuneiform; it was now accomplished.

Finally, Sumerian, the oldest language with a script, was also deciphered through the analysis of ancient Akkadian-Sumerian dictionaries and bilingual tablets.

Cuneiform had now been deciphered.

The Archaeological Remains of Cuneiform Tablets

An estimated 500,000 to 2,500,000 cuneiform tablets have been excavated in modern times, however, only around 30,000 to 100,000 have been read or published as there are only a few hundred qualified cuneiformists in the world. The British Museum holds the largest collection at approximately 130,000 tablets, followed by the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin, the Louvre, the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, the National Museum of Iraq, the Yale Babylonian Collection, and Penn Museum.

Cuneiform Literature

Thanks to now understanding cuneiform we have obtained great literary works of Mesopotamia such as the Atrahasis, The Descent of Inanna, The Myth of Etana, The Enuma Elish and the Epic of Gilgamesh. The most famous of these is the Epic of Gilgamesh. It was written in around 2100 BCE and is regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature and the 2nd oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The main themes of the text include the meaning of life, mortality and immortality, which are explored through tales surrounding Gilgamesh, King of Uruk. The original story is on 12 incomplete Akkadian tablets which were discovered in the mid-19th century by Hormuzd Rassam, a Turkish assyriologist. The gaps that occur in the tablets have been partly filled by various fragments found elsewhere.

Why is Cuneiform important today?

Without the decipherment of cuneiform lots of information about ancient history in these areas of the world would have been lost or left to extreme speculation for archaeologists. It also allows us to learn more about the world as a whole by exploring the world’s oldest writing system.

How to learn Cuneiform?

Unsurprisingly, cuneiform is not very easy to learn. It involves learning several extinct, ancient languages along with thousands of symbols and signs, some with multiple meanings and sounds. If not to make matters worse, there is not an abundance of resources on learning it due to there only being a few hundred cuneiformists worldwide. However, if you are super persistent, you can find an article on “How to write cuneiform” from the British Museum.

By Louise Bedford

Further reading:

Cuneiform – https://amzn.to/3MyvvwY

Sumerians: Their History, Culture and Character – https://amzn.to/3KilnXq

The Epic of Gilgamesh – https://amzn.to/3OznEB7

How To Write Cuneiform – https://blog.britishmuseum.org/how-to-write-cuneiform/

Leave a comment